Every year, a few days before Mother’s Day, sitting at the dining table my step-father had built for her, my mother would ask, “So, what are all of you doing for me on Mother’s Day?” My step-father, the man that raised me and I consider a full parent, would always hide his nervousness behind fabricated annoyance, “What? I have to do something for Mother’s Day?

” His Irish accent would take over the room as he chopped carrots or onions, sending my little sister and me into hushed chuckles. He was the type of dad that cooked that built furniture and gardens for his family. He was the type of husband that would pick a single rose from the rose beds he’d been cultivating for years and put them in a little vase for his wife.

He wasn’t the type to go buy a bouquet and he certainly wasn’t the type to intuitively know what present to get her.

While he was busy rummaging his mind for ideas, my sister and I would exchange thoughts in hushed tones, struggling to come up with present ideas that were representative of the size of our love for our mother. One year, we did the breakfast in bed thing, which consisted of us shoving her up the stairs and saying, “Get back to bed,” since she’d already gotten up. Another year we took her out to brunch. One year, we got her a scrub and cream, but I don’t think they were up to her French standards. She thanked us with kisses on foreheads and caresses on backs. She never used them. One year she took us to get our nails done.

It turns out she didn’t really care about, “So, what are you all doing for me on Mother’s Day?” She cared about sharing moments with us and Mother’s Day happened to be a perfect excuse for those stolen moments. She died three years ago, a month before my littlest sister’s 4th birthday, seven months before my 21st, and nine months before my little sister’s 12th. What do you do on Mother’s Day? How do you give back to your mother once she’s gone?

Growing up, I often thought of all the ways I would repay my mother for all the marvelous things she blessed me with. I was raised by four parents in two families, separated by an ocean which made it tough to figure out where I fit in within a sea of relatives from aunts and uncles to siblings. My mother was my reference, my model, the parent that reconciled the fact that I had many. She was my sense-maker. Not only did my mother give me life, as all mothers do, but she gifted me the life I cherish. Without her, I wouldn’t have met the stepfather that cooked all my dinners and cried at my good grades, I wouldn’t have moved to New York, and I wouldn’t have found my closest friends or my partner.

I often thought of all the ways I would repay her. My sister and I would often fantasize about buying her the country house she wanted to retire to when we’d be “all grown up” and have “all the money.” I’d tell my mother about all the trips I planned to take her on, “just the two of us.” This is how I conceived of paying her back for all the good she gave me. Two weeks before her death, the day after we found out she was going to die, I went to visit her in the hospital. I cried in her arms as I realized how little I knew about how much I was going to miss her and how much more I wanted to do little things for her.

“You don’t have to repay me,” she told me, as though it were the most obvious thing, “just promise me you’ll make sure you all don’t stay sad for too long.” Even in death, a mother just wants her children’s happiness.

One of the hardest parts of grief was when that happiness started to show its first glimmers. I didn’t want to be happy, she deserved a lifetime of sorrow and longing, but she also deserved what she wanted most: for us “not to stay sad for too long.” The summer before her death, I moved back home to help her reach remission but ended up moving home to help my family through collective grief and my step-father through the aftermath of losing the future he had envisioned with his wife.

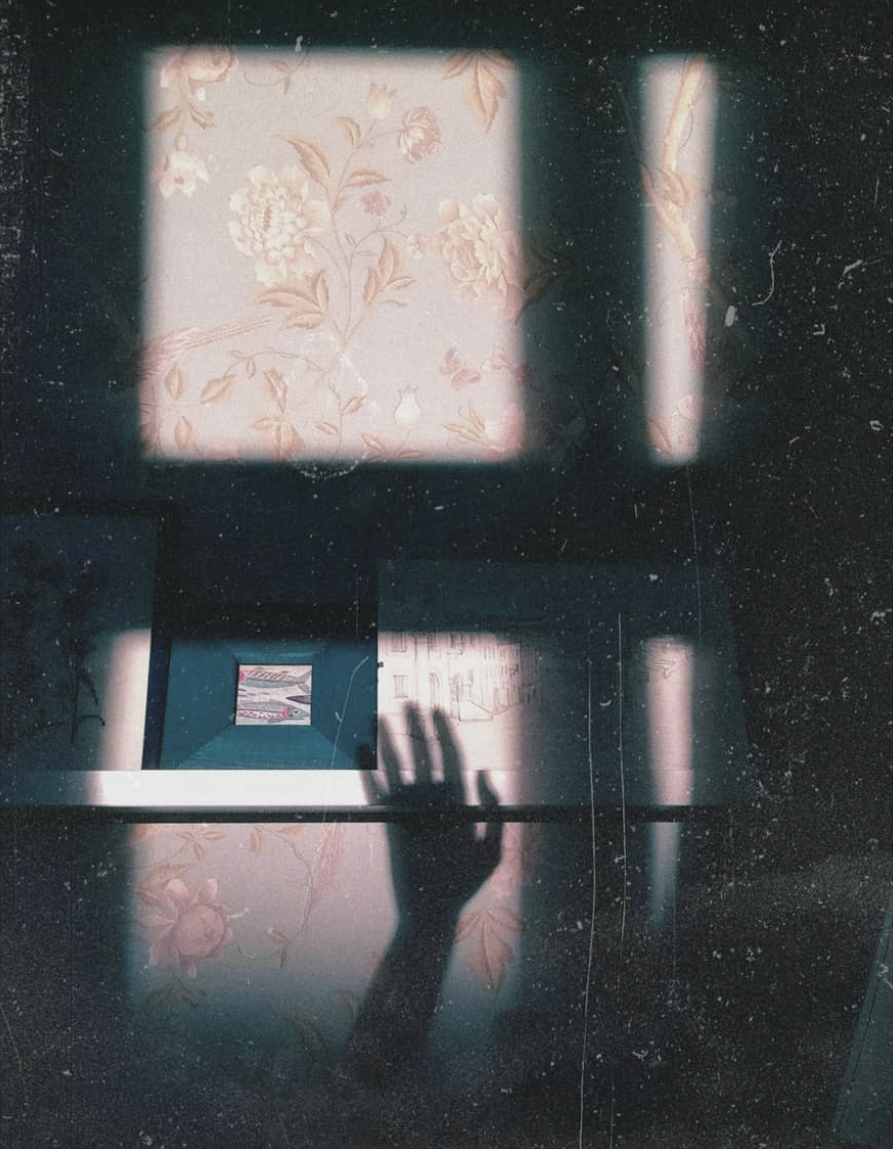

Collective grief can be grueling because you may not want to impose your bad days on your family’s good ones, but we found ways of keeping her alive in our household. From pictures to anecdotes, through imitations and rummaging through her closet, we crafted collective memory. Being the eldest, the daughter that got to spend the most time with our mother manifests in mixed feelings of gratitude and guilt. Caring for my sisters and leaning on my step-father led me to see the blessing that is being able to share all I know about our mother with my sisters. I drew my sadness out, poured my energy into transforming it so I could pass what my mother had taught me on to my sisters.

The hardest part about grief is the inability to share life with your loved one, from the toughest times to the brightest ones. Happy moments become bittersweet as you look around to find they are no longer here to witness them.

When my mother was still alive, I searched and searched for ways to give back to her, to fill her well back up. Since then, I’ve learned that the best thing I can do is fill my own, striving for joy in spite of the hole grief digs. That’s what my mother always did, a happiness expert of sorts. She taught me to choose the good and leave the rest behind. If my sisters can’t have that for as long as I did, I’ll do my best to be the model that shows them how.

This year, I’ll spend Mother’s Day with the little sisters I helped raise. We’ll share stories about our Maman. We’ll tell our littlest sister about how she’d prepare 5-star level breakfasts for us at 6 am before doing her Zumba, how the berries sat in handmade bowls, and the juices waited in carafes. We’ll tell her about how she’d tease when we’d fuss over nothing serious and say, “Oh your life sounds hard,” in a way that always succeeded in dissipating our frowns. We’ll reminisce and tell stories we’ve repeated time and time again. We’ll laugh, and hug, and cry. The littlest will use the few grief words she has access to, “I miss Maman,” and we’ll say the few words we have back, “I know, we miss her too, we’ll take care of you.”