It was never supposed to be me, at least to start. My wife was anxious, past ready to get pregnant, and I was supposed to follow a few years down the road, once our first was ready for a sibling, maybe. I’m both younger than her by a few years and gripped with panic by anything signaling discomfort, so this plan made sense.

As is the usual course of things, my wife Jenny made an appointment with a gynecologist to kick the tires and make sure everything was in good working order – which, it turns out, it wasn’t. A strange kind of ovarian cancer – stage 3c – hit the brakes on our tilt-a-whirl planning, and we skidded and screeched our way through doctors’ offices and hospital rooms. We waited, slept with loud beeps and low buzzing and the ascetic cold of white floors and walls. A few months later, a blessedly clean bill of health, and we tried to make new plans.

It took a while for the dust to settle, to even begin to trust the universe enough to consider planning for a future. I cringed through an unbearable number of well-meaning offerings of “at least you have another uterus to depend on!” as if it somehow was okay that my wife nearly died because at least our lesbianism saved us from being unable to fulfill our responsibilities as women. Sidestepping the chipper commentary so as to avoid my own tsunami of sadness and guilt tinged with just the smallest crests of hope, I spent the following year trying to convince myself that despite the volatility and the risk of being alive in bodies so vulnerable, I wanted to bet on a future. We began to officially try to make a baby.

It was a hall of mirrors: both of us annoyed at our uncooperative bodies, swept away by swells of disappointment, trying to keep the other afloat.

After the violence of Jenny’s illness, it never occurred to us to try an anonymous donor. We figured that in a world so filled with surprise, knowing exactly what we were getting (to the best extent possible) made the most sense, and when it comes to love, more is more. Over a New Year’s Eve weekend summit at a rented farm in upstate New York, we asked Jenny’s best friend and former roommate if he and his husband would consider donating sperm. Alternating between bundled up walks along dirt roads and celebratory champagne, the weekend did not yield an immediate yes – we collectively considered the implications, and we discussed what it would like for the four of us to parent a child. Over time, an agreement grew and developed. We tossed around a series of hypotheticals, navigated some tense terrain through a series of purposeful, careful conversations, and signed some legal paperwork delineating responsibility.

One spring weekend, we started the process of trying to get pregnant the old fashioned way – with a needless syringe, a few bottles of Prosecco, and an obsessive fertility-tracking app on my iPhone. I was so anxious the next day that I made myself sick and then convinced myself I had morning sickness.

At some point in that first month, my best friend (recently pregnant herself) advised me to make an appointment with a fertility doctor – because it would take forever to get an appointment and if I didn’t need it I could cancel. After six months of no luck, it was time to meet with a very nice, very clinical older white man, who told me in the clearest possible terms that I have a Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, and getting pregnant would be challenging. We began the fertility slog: months of meds to regulate ovulation, blood draws to check hormone levels, shots in my abdomen to trigger egg release, insemination in the doctor’s office with our donor’s frozen sperm, a few heartbreakingly hopeful moments, a D&C to remove a polyp, and the bitter segmentation of our lives into two week blocks of waiting on a moving target.

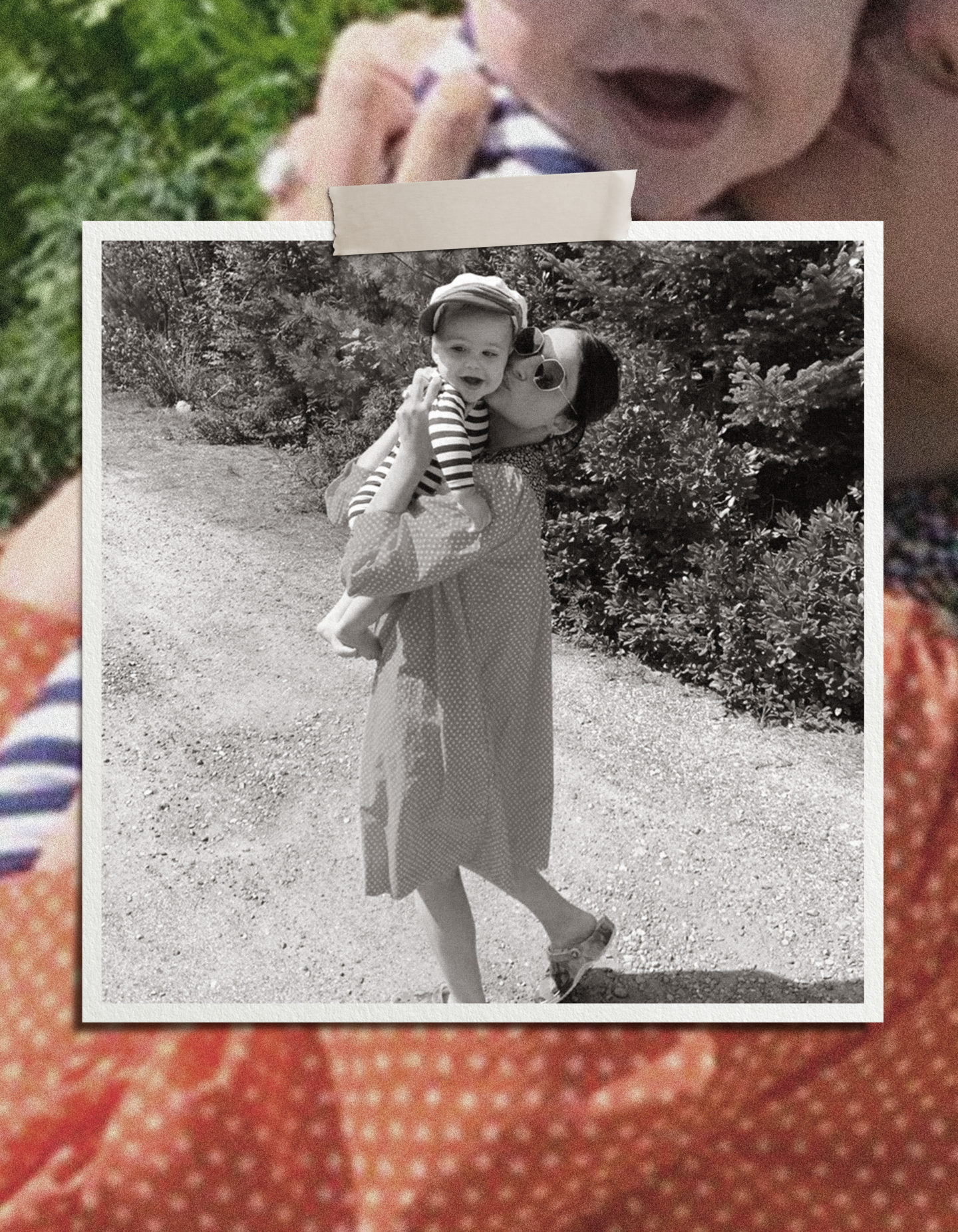

All photos courtesy of Kenne Dibner

I recognize how ridiculous this sounds, but never before in my life had I been unable to just make something happen for myself. I just… worked hard, and all the things I wanted happened. In my whiteness, my economic privilege, and general plucky can-do attitude, I had never before encountered a problem I couldn’t solve by just setting my mind to it. I was unmoored by my lack of success, unhinged, all unfiltered rage at the fact that it wasn’t even supposed to be me getting pregnant in the first place. I had nowhere to go with my frustrations but a wife who was, kindly, generously, trying not to make this moment about her inability to do the thing. It was a hall of mirrors: both of us annoyed at our uncooperative bodies, swept away by swells of disappointment, trying to keep the other afloat. In the end, Jenny led with selflessness, holding my sadness while also keeping us on board, oriented North. One last time, she said, and we’ll talk about a different plan.

Fourteen days later, I woke up, dutifully peed on a mockingly perky pink and white stick, handed it to my wife, and told her since I wasn’t pregnant to wake me up in a half hour. When you wait for months to get pregnant, you spend hours on the internet, stalking random Reddit threads of other desperate TTC women, so exhausted by the process that no one can bear to type out Trying To Conceive any longer. We are all frantically looking for early signs of pregnancy: discharge? Good sign! Tired? Likely pregnant! Dry skin? Could be, who knows, don’t give up hope! That month, I had no such signs. In fact, I had been in San Antonio with my two best friends in between insemination and testing, knowing in my heart that I wasn’t pregnant, and quietly calculating how we would afford IVF.

My wife screamed. A joyful, NO REALLY YOU’RE PREGNANT scream. Annoyed, I told her it wasn’t cute, and then cried, and then peed on another stick. 180 seconds later, more screaming, tears, and frantic phone calls to arrange a blood test. Later that afternoon, oddly high levels of hCG, the hormone indicating pregnancy. It tripled in 24 hours, tripled again 24 hours later. An early ultrasound detecting two distinct embryos, and my dedicated OBGYN sweetly insisted that I say something – anything – before letting me off the exam table. The rest of that day is all streaky adrenaline, the sharp crack when the heat of anticipation is plunged into an icy present. We tried to make new plans.

For a story with a zillion false starts, this would be the first one that stuck. We now have 16-month twins, and I know we should be aggressively and carefully planning for the future. But right now, in the midst of the shrieky chaos of two toddler comets at full blast, I’m just so grateful there’s a future to plan for.